Conservation Concept: Extinction Panic Explained

What's the deal with extinction rates?

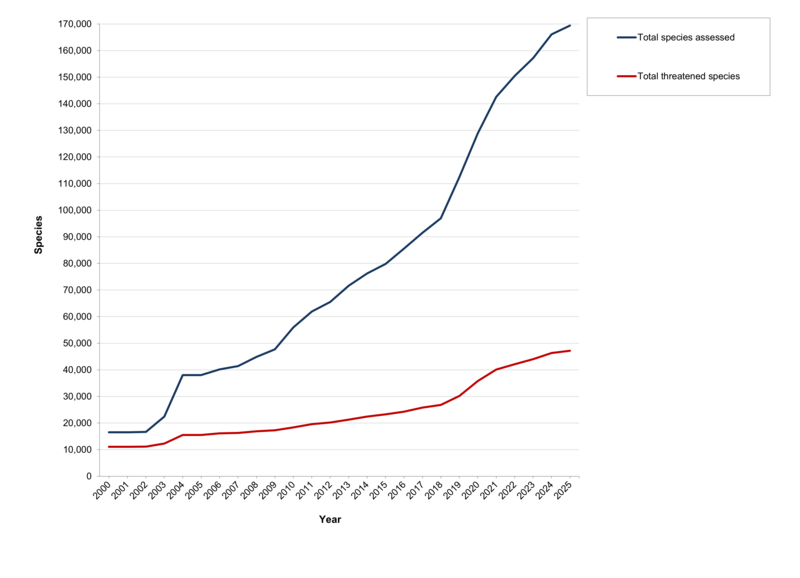

Since we've started tracking species populations, we've noticed an alarming trend: an increase in extinctions, and proliferation of newly threatened species. Conservation organizations are quick to point out threats to charismatic megafauna like pandas and rhinos, but habitat loss and species loss have indiscriminate widespread impacts to the point where some are calling the current losses part of a mass extinction event... something that has occurred only five other times in Earth's 4.5 billion year history.

What exactly is mass extinction? Let's dig into how scientists think about extinctions and how what we are experiencing today stacks up against previously documented worldwide extinctions.

Looking Back

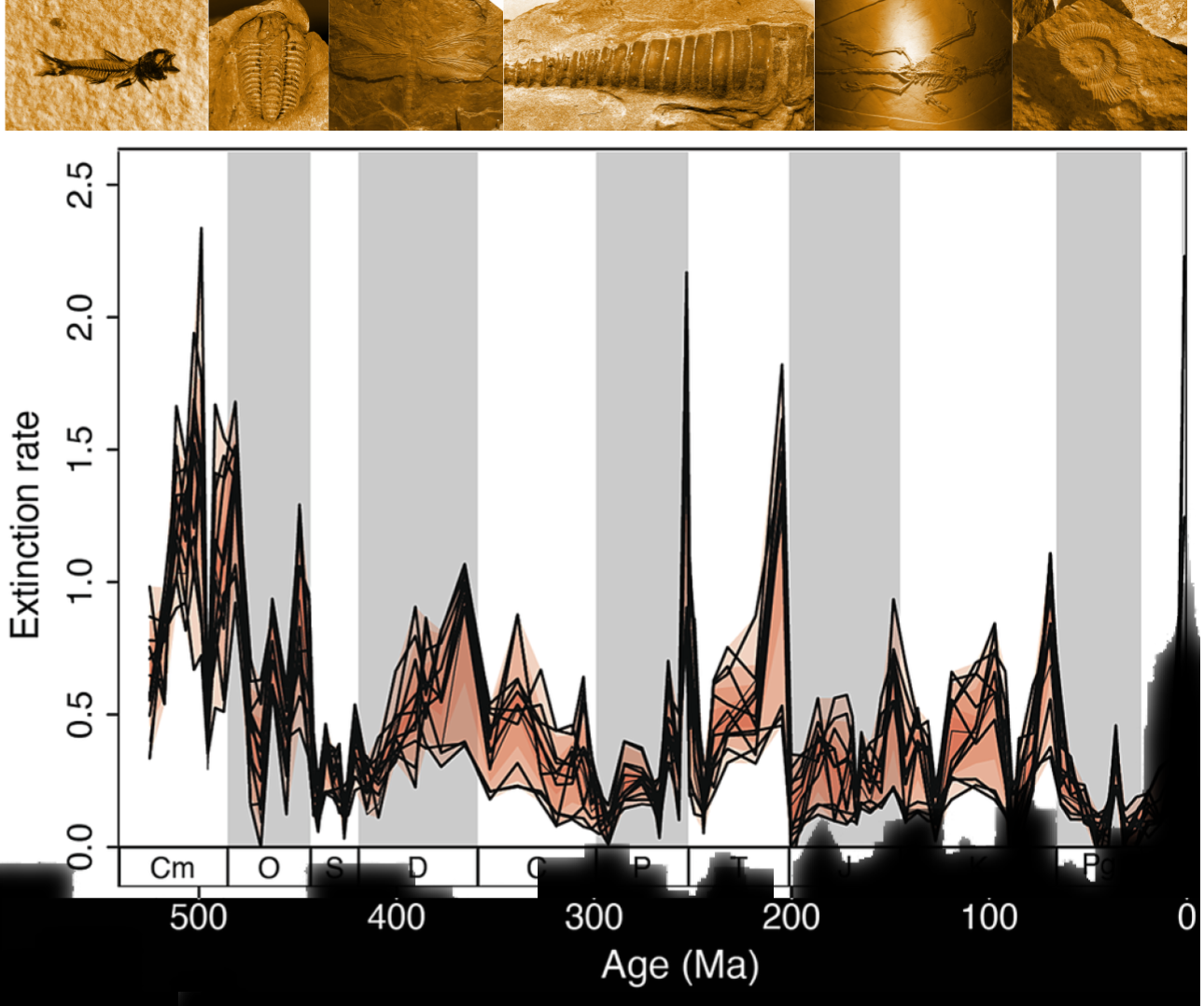

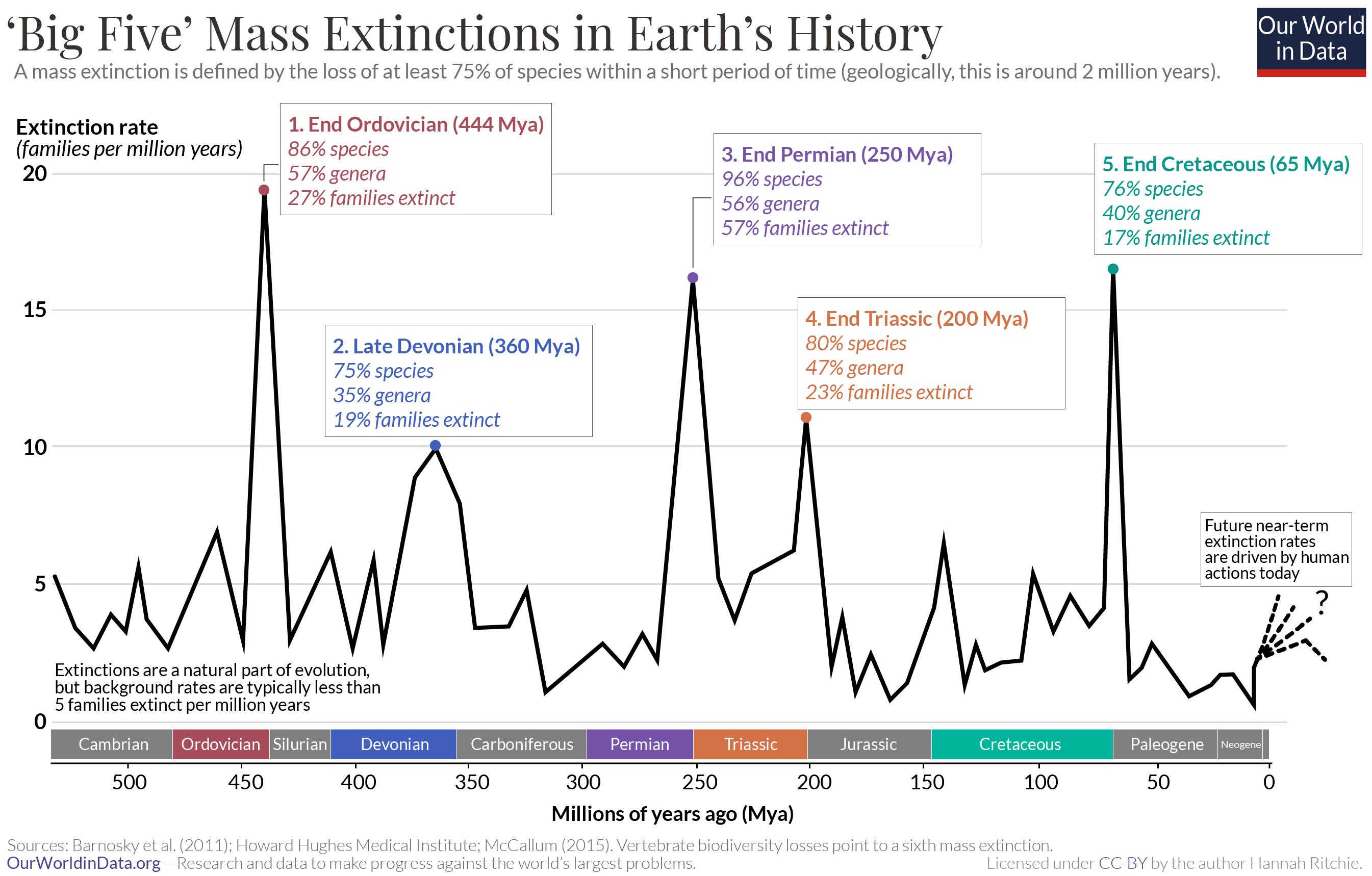

One of the coolest things about natural science is how different fields overlap and connect. An uncommon, yet important connection links geology/paleontology and conservation biology when scientists learn about current trends in biodiversity through observations from our geologic past. Fossil records can track the appearance, evolution, and disappearance of species over millions of years. Compiling these findings has lead to some interesting conclusions about historical biodiversity. Several times throughout the history of earth, species have been obliterated from the fossil record, over a relatively short time period. These mass extinctions have wiped out the majority of life, often upwards of 50%-75% of living species at a time. Five previous mass extinction events have been identified, observed through marine fossils.

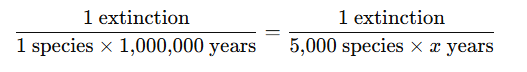

With the ability to identify and track fossils through time, we not only know when big events happened, but can also make general assessments, like estimating the number of species that existed during stable periods without mass extinctions. Using those species counts, we can calculate a baseline extinction rate for different eras and we observe the rise and fall of different species. This gives scientists a rough benchmark against which to compare what we’re experiencing in contemporary times. This can be expressed as Extinction Rate per Million species year. More on that in a second.

To illustrate, scientists think the average span of existence for a mammal species is around 1 million years, and with a little more information can figure out extinction benchmarks.

We know of roughly 5,000 distinct species of mammals in existence today. Given the above example of extinction rates (1 extinction of 1 species / 1 mil years), we'd expect 1 extinction per 5000 species every 200 years.

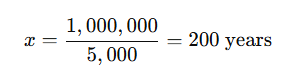

However, over the past 400 years, 89 mammalian extinctions have been documented, with a growing list of endangered species on the brink. This is well-above the expected background rate for mammals.

Birds, fish, invertebrates, plants, fungi, each will have their own ambient rate of extinction, and scientists are working on calculating these rates with increasing accuracy. Not only are extinction rates increasing, the rate of extinction is accelerating over time.

Looking Forward

Current extinction rates are outpacing naturally expected rates, and this is why scientists are sounding the alarm on a potential mass extinction. But it's early, geologically speaking. Meanwhile, some paleontologists are still debating the severity of the five previous mass extinctions for terrestrial species. Plants may have been unaffected during four of the events. And even though an asteroid ended most dinosaurs, crocodiles and sharks survived, dinosaur descendants of birds survived, along with mammals, casting some doubt on the severity of that extinction event for different groups of animals. If these claims can be further supported, the current elevated extinction rates might be the start of the first truly widespread extinction event on land, driven by yours truly, Homo sapiens (people).

It's unfortunate to boil things down to simple calculation of a net species plus or species minus. If we claim to have prevented a mass loss of 50% of all species, we still pretty much failed at meeting any current conservation goal. And counting species losses numerically seems illogical outside of a geologic perspective. Losing one keystone species (a species upon which other species largely depend) would have greater negative impacts on its ecosystem compared to losing one a non-keystone species. But, if the calculus only considers species lost, they all count equally.

Can we call it a mass extinction event? That might be semantics. Whether we’ve crossed the threshold or not, the trajectory is clear: the rapid decline in biodiversity is untenably tied to human activities.

It's easy to discount the past extinctions as acts of god, driven by volcanic eruptions altering the climate, or cosmic coincidences, but when it happens as the direct consequence of humanity's callous actions, the pill feels harder to swallow and will ultimately lead to our own demise.

Enjoy this article? We need your help funding conservation and science reporting, fly fishing deep dives, and more stories from the road.

Every contribution helps support conservation and scientifically informed writing on fish.