Useful Biology: Hacking Camouflage

Countershading is found in almost all fish, how can we use this to our advantage as anglers and fly tyers?

February 2026

Whether hunting or hiding, camouflage plays a key role in any fish's ability to survive. The last thing a baitfish needs is to stand out against their school, that's the fastest way to get eaten. All fish need to blend in. Luckily, natural selection has refined coloration over generations of trial and error, and savvy anglers can learn a lot about how fish hunt or hide; even how to design flies just by understanding how fish use their camouflage.

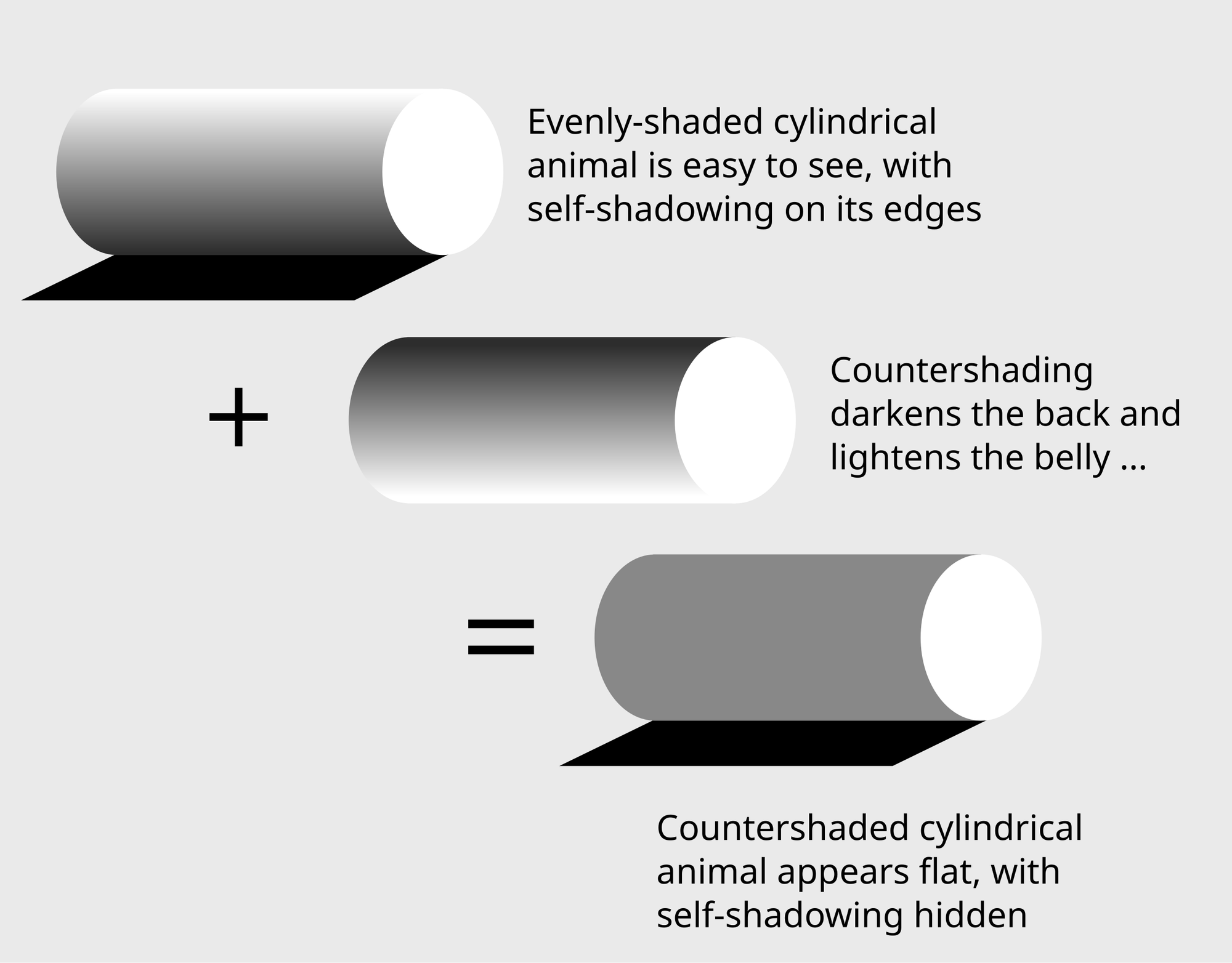

Countershading, a camouflage where an object is darker on top and lighter on bottom is common amongst many fish. In 1909 Abbott Handerson Thayer discovered that countershading is a widespread phenomenon in the natural world, and seems to have evolved to counteract the natural self-shading effect of overhead sunlight. When light falls on an object from above on a three-dimensional uniformly colored object, a gradation appears making the top of the object appear lighter, and the bottom of the object darker. To counteract the self-shadowing, fish developed darker dorsal patterns compared to lighter lateral and ventral shading (their sides and belly). The result is a fish that appears less 3-dimensional and more flat, helping to blend into their surroundings, instead of standing out.

Examples: Countershading

Pike like to live in weeds, so naturally they take on an appearance to match their surroundings. Their camouflage necessarily reflects their habitat preferences, and also indicates their hunting style: blending in before ambushing prey.

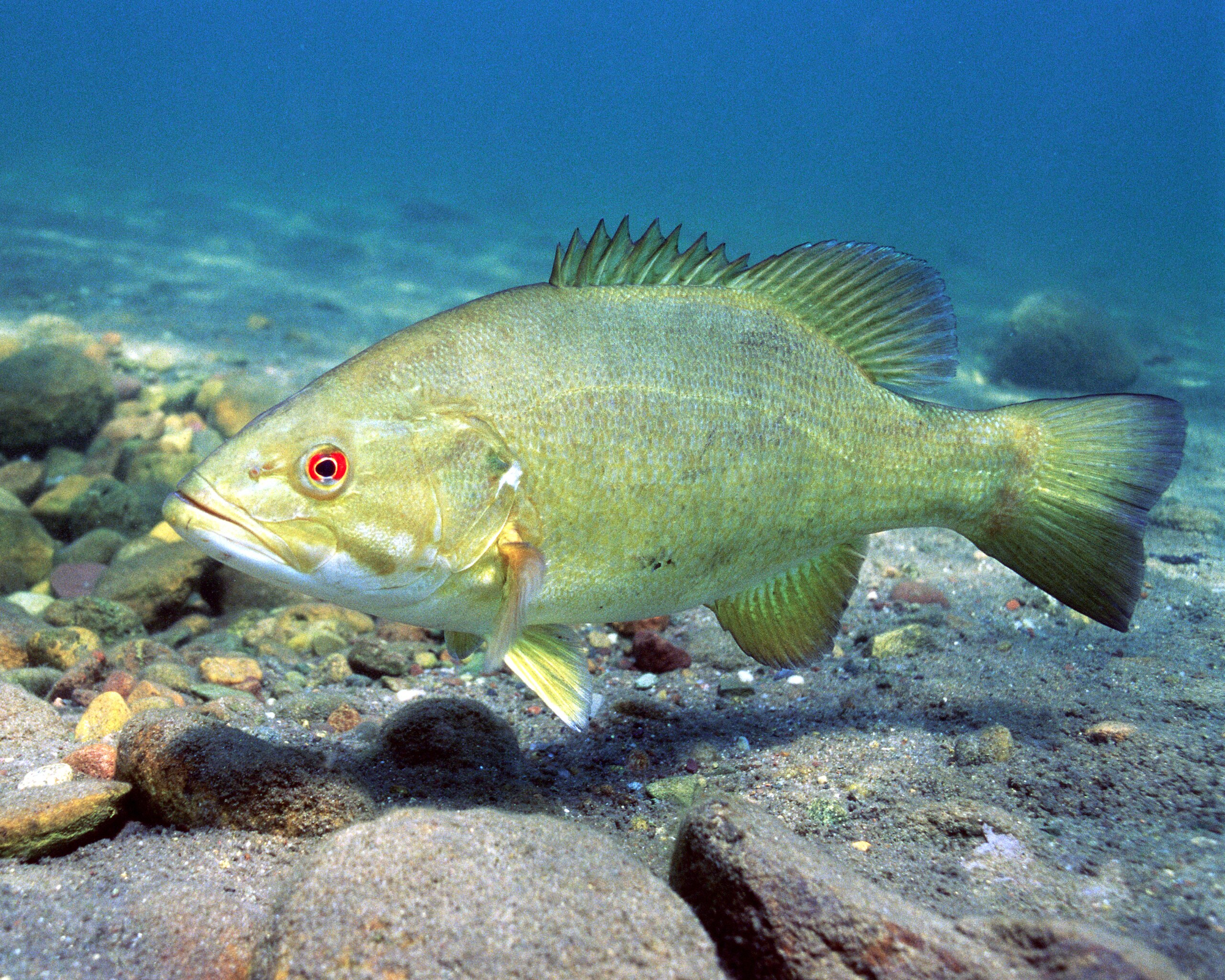

Sometimes you'll find smallmouth bass that are light olive, almost lime green, these fish are likely hunting in brighter sandy habitat where the countershading is less pronounced, at least compared to the dark rusty smallmouth you may pull out from behind sunken logs.

Fish can use special pigmentation cells called chromatophores to alter their colorations (lighter vs darker, spawning colorations)

If gamefish are so effectively colored to match their habitat, don't you think their forage would as well? Knowing this, fly tyers can take advantage of the countershading phenomenon. Pike, smallmouth, and trout (as examples) are all geared towards eating prey at eye level or above them. This suggests that lightly-weighted streamers (that would be seen from predators below) should generally match the underside of their prey. Meanwhile, if presenting flies deeper where a predator may see the whole profile of the prey, a two-toned dark over light fly may be more appropriate. Finally, if presenting prey deep, like a crayfish jigged on the bottom of a river, dark colors feel most appropriate.

Theoretically, a smallmouth bass focused on crayfish may take all three types of flies, light colored, two toned, and dark colored. It all depends on how you present the pattern.

Example: Fly Tying

If your jigging a heavily weighted sculpin pattern, make sure the sculpin fly coloration matches the dark profile of the naturals, who will be well camouflaged to the colors of the riverbed. Alternatively, if you're wanting to fish a baitfish pattern swung that rises through the water column, you'd be better off fishing a pattern that highlights the light colored belly, the likeliest viewpoint from a predatory fish.

In fact, you might tie certain flies that are only meant to look like the belly of the prey, forgoing any dark coloration altogether. More interesting: gawdy attractor flies may even make sense for matching underbellies or spawning colors of various forage fish.

Would the Mickey Finn (yellow and red) be appropriate for matching the spawning colors on a Redside Shiner, indigenous in Yellowstone National Park? What does the predatory cutthroat trout see if attacking a Redside Shiner from below? I'd argue they see mostly an underbelly of silver/white, yellow and red.

Matching the exact hatch is such a dominant idea for anglers coming from the trout school of fly fishing that sometimes it blinds us from thinking outside that box.

Uniform Coloration in Flies: Advantage or Disadvantage?

An interesting side effect from this phenomenon is how uniformly patterned objects (no countershading) stand out to predators. Without countershading, a predator's ability to detect prey depends more on background conditions, and is easier to identify.

Would this suggest that solid colored flies are taken more readily, as they can be picked out more often by predators? Or maybe, when it's hard to get a bite, solid flies become too obvious and stand out as imposters?

Streamer anglers have lots to consider, but almost all predator/prey interactions are rooted in identifying and outwitting the opponent's camouflage.