Nymphing vs Turbulence

The nymphing angler is locked in a perennial quest to fish deeper because rivers fight back...

June 2024

Since shedding the "dry or die" mantra of old school fly fishing, the focus shifted to fishing flies deeper. For good reason, too. As I'm sure you've heard before, 90% of all trout feeding happens subsurface. The first wave of nymphs gave us classic flies like the iconic pheasant tail, introduced in 1958 by Frank Sawyer. But that wasn't good enough, we need to go deeper! Then came the beadhead nymph, which swept across the fly fishing world by the 1980s. Though the originator may be disputed, before long, the beadhead nymph was helping anglers fish their nymphs deeper than ever. Again. But we weren't done. By the 1990s, John Barr invented the Copper John, adding further weight to nymphs by doubling down on a beadhead chassis with copper wire wrapped along the hook shank. Quickly, the Copper John became Umpqua's top selling pattern world wide.

The trend continues even today. Now that euro-nymphing has gone mainstream, you'll readily come across flies like perdigons which have again taken nymphing to new heights, or is it depths... with low friction epoxied bodies fished on light thin tippets, the perdigon is presenting flies deeper than ever.

At every step along the way we've been catching more and more fish. Is that why we search for heavier flies and techniques to effectively fish deeper? The nymphing angler is locked in a perennial quest to fish deeper, but why?

Because rivers are constantly fighting back.

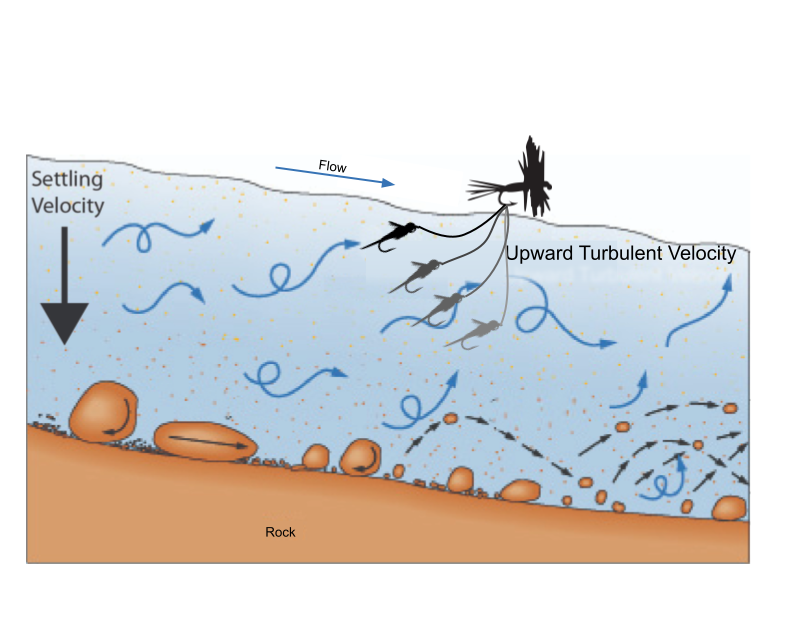

Fighting More Than Gravity

Turbulent forces within rivers complicate the downward trajectory expected from our weighted flies. Turbulence creates whitewater, forces rocks tumbling downstream, and mobilizes small particle during runoff, but we usually only consider flow in one direction, from upstream to downstream... this only addresses the larger pattern of the river. We largely ignore the microcurrents, the small complex swirls found by close examination of specific rocks and eddies. Even anglers apt at reading water may still overlook one particular form of microcurrent: upward turbulence.

As a thought experiment, consider runoff. During runoff, tiny particles like sand and silt elevate from the streambed and become visible even at the surface. The change in river color (i.e., chocolate milk) illustrates the multitude of micro-currents churning every direction (including towards the surface), strong enough to create turbid waters. Do we, as anglers, consider these microcurrents, specifically those that swell upwards? How well do we consider split shot or heavier flies to counteract these effects? I'd argue that we don't acknowledge this upward movement enough, and that's partially why we're all repeatedly infatuated with new, heavier nymphs.

We tend to think our nymphs drop (more or less) directly under our indicators, or directly under our dry flies. But upward velocity within a turbulent river may impact the drop rate of the weighted nymphs. When picturing your nymph tumbling downstream, without enough weight to overcome stream velocity, your fly may get carried off by tiny current swells; never fully reaching depth. Obviously, the lighter your fly, or heavier the current, the stronger the effect. More influential; the size of rock on the streambed.

Fortunately, this phenomenon is easy to pattern and directly relates to the composition of the riverbed. Larger rocks, like boulders and cobblestones resist against the onslaught of downstream flow, redirecting water around resistant rock and forcing water to adjust to a path of least resistance. Think about which direction water redirects off a wall when shot out of a hose. The same thing is happening in rivers. In these rocky sections, identified by roiling rapids, rock-gardens, or even riffles, microcurrents can redirect the movement of a weighted fly.

On the other end of the spectrum, in areas where fine sand makes up the riverbed, you see these effects reversed. In these situations, there are less collisions between fast moving water and resistant rock, creating smoother flow for weighted flies to easily deploy.

Strategies

- If you're struggling to produce fish in areas with larger rocks and cobble, consider additional weight

- If you're fishing over sandy bottom, heavy weight may be overkill

- In-line rigs, flies connected hookbend to eye, may ride microcurrents more naturally, but may struggle to stay in the same seam if length of the chained flies is too long

- Dropper flies tied as tags are free to dance in microcurrents without getting pulled out of the strike zone

- Longer tippet and lighter flies = more movement, shallower, harder to replicate drifts over repeated casts

- Shorter tippet and heavier flies = less movement, deeper, easier to repeat casts into the same feeding lane

Want to learn more about where to find trout in a river?

But Don't We Want Our Flies To Dead Drift?

Why should we even worry about our flies riding microcurrents? If the current wants to move a fly upward in the water column isn't that an accurate dead-drift presentation?

It all depends on where fish are holding. If fish are looking for dries, emergers, or are holding higher in the water column, you probably don't want so much weight that your fly isn't dancing in the microcurrents at least a little. Upward turbulence may even benefit anglers fishing hatches with soft hackles or lightly weighted nymphs. Given the right flow conditions, emerging bugs may surf these microcurrents towards the surface during their emergence. And yet fish would rather hold deeper where they will undoubtedly look for the easiest meal, so a nymph presented slightly deeper in the column may entice a trout looking to save some energy. There are no absolutes in trout fishing.

Still, this concept may help in surprising situations. I keep thinking about one particular run on the North Platte where large rolling waves accentuate large rocks on the stream bed. It’s brisk moving water, but leads into a calmer stretch of water where fish stack into the run to feed and relax into the calmer water to rest. This run is always difficult to fish deep enough, and no matter what, I often feel like I could present flies deeper. Here we might not see the obvious signs to increase weight on our rig. Sometimes we only think about adding weight in deeper water. From experience, especially with elevated flows or when fish are holding close to the bottom, we need to take greater measures to get our flies to the strike zone. Then factoring in chaotic turbulence and water colliding on itself, that might mean adding as little as one more split shot than you think.

Effective nymphing comes from trial and error, experience, and a willingness to re-rig. Maybe a quick examination of the rock size under your feet could give you the extra information you need to hook up more consistently while nymphing.

Sources:

- Hosain, A. 2020. Famous Fly Origins: The Pheasant Tail. 2020. Fly Lords. https://flylordsmag.com/famous-fly-origins-the-pheasant-tail-nymph/

- M. Roman. 1996. The history of the gold bead. Global Fly Fisher. https://globalflyfisher.com/patterns-tie-better/the-history-of-the-gold-bead

- Giannino, R. 2019. Theo "Gold Bead" Bakelaar. Fly Fishing Journeys. https://flyfishingjourneys.com/theo-gold-bead-bakelaar/

- Huff, W. Accessed 2024. Sedimentation. https://homepages.uc.edu/~huffwd/Sedimentation/Sedimentation.htm

- National Park Service (NPS). 2022. Sediment Sorting. https://www.nps.gov/teachers/classrooms/sediment-sorting.htm

- Kunaka, D. 2023. What Is the Hjulstrom Curve. https://thegeoroom.co.zw/hydrology/the-hjulstrom-curve-of-river-erosion-transportation-and-deposition/

↓Bonus Material↓

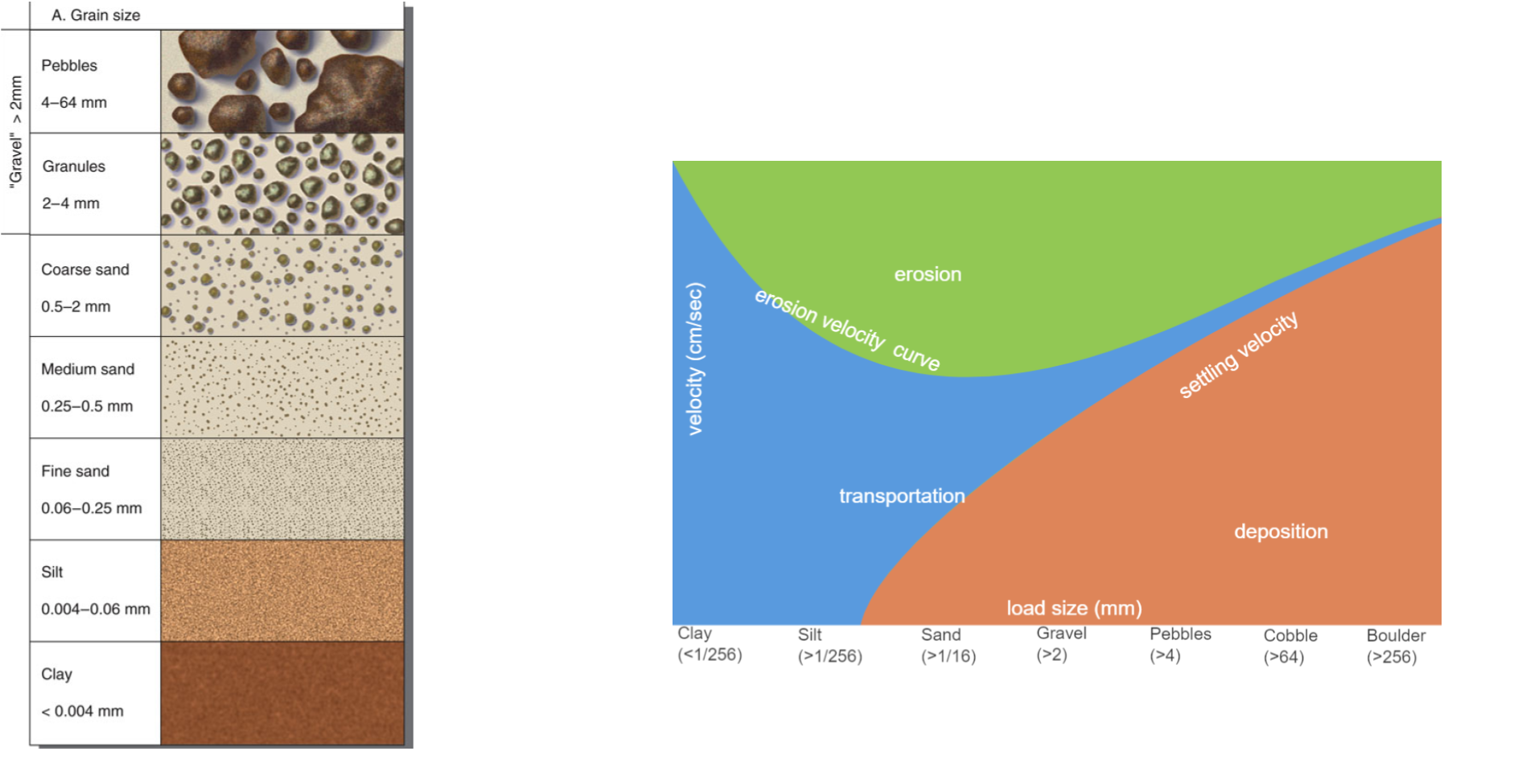

How Much Weight Is Enough?

In the realm of hydrology, you can calculate how much stream velocity is needed to mobilize certain sized rocks, pebbles, or other grains. And that's essentially what we're dealing with here, but while hydrologists might be interested in grain size, anglers can instead think of fly size, bead size or split shot size. There's a relationship between how large a river item is and how much flow is needed to sweep that particle out of its resting position. The bigger the item, the more flow needed to transport the item. Like Isaac Newton said, "Every object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless compelled to change its state by the action of an external force." Anglers should be able to get away with (somewhat) large flies that might otherwise want to settle since they're not starting from a rested position on the streambed, they're starting from a roll-cast plunging into likely holding water.

If you're fishing two equally sized beadhead nymphs thinking that the combined weight between the two will help overcome velocity challenges, consider that the velocity affects both flies in the same way. Meaning, if the velocity is strong enough to move one of your flies, the same will happen to the other fly, preventing any additive power of having more weight on your rig. A better setup would be having one heavy fly that isn't as mobilized by flow, and a smaller dropper tied in as a tag above the heavy fly. Or two flies heavy enough to both counter the current.

Fortunately, there's some wiggle room in this relationship. As current flows faster at the surface than at the stream bottom, an indicator helps buoy heavy flies, keeping them moving when they might otherwise want to settle on the river bottom. These heavier than average rigs help you cut through the swirling microcurrents as well. The key is to keep that indicator from moving too quickly, which would speed up and disrupt the way your deep fly bounces along the bottom. Simultaneously, if you overload your fly with weight, a drift won't even be possible. Indicator nymphing is an intricate dance developed out of experience.