No, Trout Aren't Lazy

Fly fishing: They say to look for areas where trout can indulge in their 'lazy' tendencies. One problem — trout aren’t lazy!

September 2020

It wouldn’t take an in-depth Google search to find an article proselytizing the laziness of trout. Maybe the articles are meant to guide anglers and newcomers on how best to find trout in rivers. "Look for the slowest water," they say. More specifically, "Look for areas where trout can indulge in their 'lazy' tendencies." One problem — trout aren’t lazy! A lazy trout would be one unwilling to engage in the perpetual treadmill of living in a river. A lazy trout would be one not actively feeding... a lazy trout would be skinny and malnourished.

Trout are optimizers; they are incredibly adept at gauging the energy requirements of their environment and responding in a way that maximizes the amount of energy that can be sequestered for the smallest amount of effort. Trout don’t work harder, they work smarter. When temperatures climb into a trout’s optimal feeding range (see our article about ideal temperature ranges for trout), and when hatches are abundant (common during the summer months), a trout can be found feeding in surprisingly quick water. They move out of their pools into the fast-food conveyor belts of riffles. They might have to fight a swifter current as the velocity is greater in riffles, but the food is so abundant that the energy gain is still worth the energy expenditure (Naman et al., 2017). Macroinvertebrates thrive between river rocks in the velocity breaks provided by that interstitial space. This inevitably leads to either behavioral or accidental drifting of insects downstream, and the trout know how to position themselves accordingly. After all, they live it day-in and day-out and quickly capitalize on dislodged prey.

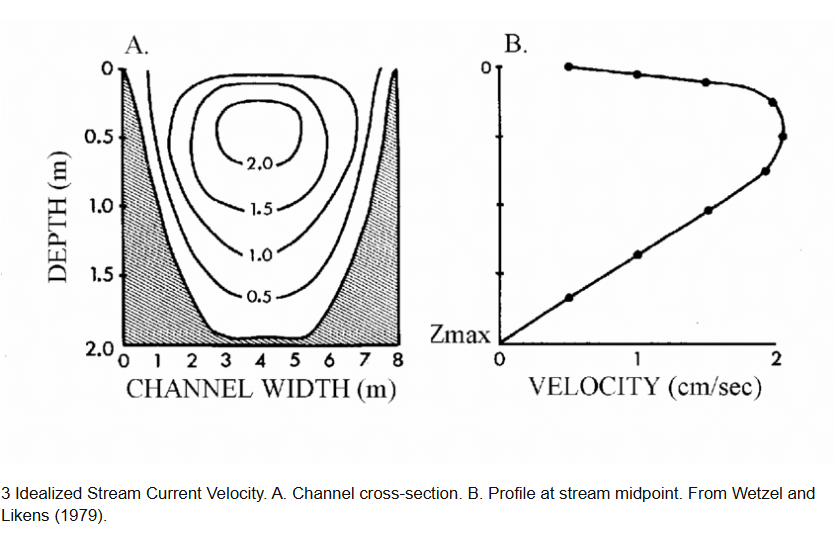

Stream hydrodynamics can make things confusing to anglers approaching a fast-moving stretch of water. Though surface currents may appear to produce rapidly moving water, the velocity on the stream bottom is much slower. This allows fish to steadily hold in seemingly quick water when the energy cost is surprisingly manageable. The above figure shows how velocity changes in a 3-dimensional cross-section of a river. Take note of how low the velocity is at the streambed.

Interestingly, different species do have varying behavioral tendencies. For instance, rainbow trout are more focused on energy acquisition and are typically more likely to brave faster water for an ideal spot on the fast-food conveyor belt. Brown trout, on the other hand, are much more focused on energy conservation. They tend to feed in slower water, along banks, and places where the energy cost is significantly less (Gatz et al., 1987). But don't be mistaken, though they prefer slower velocities, they still strike on high-calorie food items when presented.

If you’re interested in learning more about trout behavior through the eyes of a successful angler, we suggest reading "Tactical Fly Fishing" by Devin Olsen. He similarly presents angling advice rooted in ecology and science. Even if you’re not into the competitive angling tactics, the first three chapters of his book are worth the read by themselves.

Sources:

1. Wetzel & Likens. 1979. 3 Idealized Stream Current Velocity. A. Channel cross-section. B. Profile at stream midpoint.

2. Naman, S.M., et al. 2017. Habitat-Specific Production of Aquatic and Terrestrial Invertebrate Drift In Small Forest Streams: Implications for Drift-Feeding Fish. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, vol. 74, no.8. 1208-17.

3. Gatz, A.J., et al. 1987. Habitat Shifts in Rainbow Trout: Competitive Influences of Brown Trout. Oecologia, vol. 74, no.1 7-19.

4. Olsen, D. 2019. Tactical Fly Fishing: Lessons Learned from Competition for All Anglers. Stackpole Books.